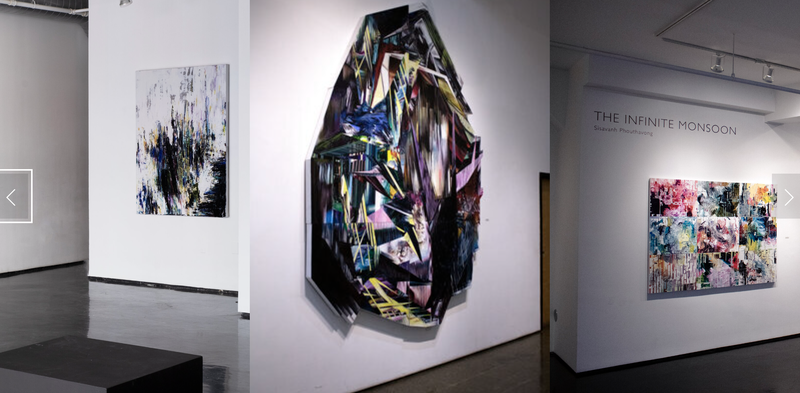

January 23rd-Feb. 27th 2020: "The Infinite Monsoon" Solo Show: Tinney Contemporary Gallery, Nashville, TN

www.tinneycontemporary.com/past-exhibitions/k7m092ko76jupz7af5fwznfo65vyvg

www.tinneycontemporary.com/past-exhibitions/k7m092ko76jupz7af5fwznfo65vyvg

Sisavanh Phouthavong lives and works in Murfreesboro, TN. She is a professor of painting at MTSU and has received considerable recognition for her work. Her work draws heavily on her experience of displacement as a Lao American refugee. These large scale, abstract paintings create a third space of cultural hybridity, of fractured perspective and identity—a space where the artist’s Lao identity coexists with her American identity, where landscape might be written according to the artist’s own experience rather than by supposedly objective power-structures.

Each piece seems to resist traditional ways of seeing—the viewer is met with not one focal point but many; perspective is thwarted by the kaleidoscopic internal rhythms which create not one horizon, but many. Her work does not (to borrow from filmmaker Hito Steyerl) “assume an observer standing on a stable ground looking out towards a vanishing point on a flat, and actually quite artificial, horizon”—instead, she contravenes (white, western, patriarchal) art-historical notions of perspective in order to inscribe a new gaze—her own way of seeing.

Phouthavong rebels against a post-colonial regime of “looking” by dispersion and fragmentation. Standard canvas dimensions are abandoned for asymmetrical geometric forms better suited to describing Phouthavong’s vision. Each work is experienced as a landscape of sorts, despite the lack of recognizable geological features, but the mapping of space that occurs is not dictated by fidelity to some objective. Instead, the power lies with the subject—with Phouthavong in creating the work, and perhaps with the viewer in their recognition of subjects capable of constructing their own worlds from the fragments of identity (maybe, as Whitman said, we all “contain multitudes”). In her smaller mixed-media pieces, you are driving across a mosaic of cracked ground. White dashes of street lines overlap, seem to converge at any number of “vanishing points.” And yet, while the pieces seem to contain a sort of violence—the jagged angles and sharp contrast between colors—there is also an intricate beauty. Phouthavong has pieced together a mosaic of her own experience; overarching the tension within each piece is the unity of the whole.

Phouthavong’s way of looking is personal, yet shared, emotional, yet rooted in collective identity spanning space and time. The effect of these radically personal landscapes is Utopia, “no-place”—a home, but not a physical one; a diasporic unity, created from the fragments of post-colonial identity, the violence of civil war as well as the inner-conflict between competing cultural claims. And it is an atmosphere the viewer can enter and experience—thanks to the life and newness Phouthavong has imbued in each piece.

Each piece seems to resist traditional ways of seeing—the viewer is met with not one focal point but many; perspective is thwarted by the kaleidoscopic internal rhythms which create not one horizon, but many. Her work does not (to borrow from filmmaker Hito Steyerl) “assume an observer standing on a stable ground looking out towards a vanishing point on a flat, and actually quite artificial, horizon”—instead, she contravenes (white, western, patriarchal) art-historical notions of perspective in order to inscribe a new gaze—her own way of seeing.

Phouthavong rebels against a post-colonial regime of “looking” by dispersion and fragmentation. Standard canvas dimensions are abandoned for asymmetrical geometric forms better suited to describing Phouthavong’s vision. Each work is experienced as a landscape of sorts, despite the lack of recognizable geological features, but the mapping of space that occurs is not dictated by fidelity to some objective. Instead, the power lies with the subject—with Phouthavong in creating the work, and perhaps with the viewer in their recognition of subjects capable of constructing their own worlds from the fragments of identity (maybe, as Whitman said, we all “contain multitudes”). In her smaller mixed-media pieces, you are driving across a mosaic of cracked ground. White dashes of street lines overlap, seem to converge at any number of “vanishing points.” And yet, while the pieces seem to contain a sort of violence—the jagged angles and sharp contrast between colors—there is also an intricate beauty. Phouthavong has pieced together a mosaic of her own experience; overarching the tension within each piece is the unity of the whole.

Phouthavong’s way of looking is personal, yet shared, emotional, yet rooted in collective identity spanning space and time. The effect of these radically personal landscapes is Utopia, “no-place”—a home, but not a physical one; a diasporic unity, created from the fragments of post-colonial identity, the violence of civil war as well as the inner-conflict between competing cultural claims. And it is an atmosphere the viewer can enter and experience—thanks to the life and newness Phouthavong has imbued in each piece.